Beyond Ishtar: The Tradition of Eggs at Easter

Eggs occupy a special status during Easter observances. They’re symbols of rebirth and renewal—life bursts forth from this otherwise plain, inanimate object that gives no hint as to what it contains. In this regard it is a handy symbol for the resurrection of Jesus Christ, but it is is a symbol that has held this meaning long before Christianity adopted it.

Ishtar the Babylonian goddess of fertility and sex.

There is a meme floating around Facebook that some people have rallied around and are sharing as a “truth” of Easter. It proclaims:

Easter was originally the celebration of Ishtar, the Assyrian and Babylonian goddess of fertility and sex. Her symbols (like the egg and bunny) were and still are fertility and sex symbols (or did you actually think eggs and bunnies had anything to do with the resurrection?) After Constantine decided to Christianize the Empire, Easter was changed to represent Jesus. But at its roots, Easter (which is how you pronounce Ishtar) is all about celebrating fertility and sex.

Clearly, we all know that Facebook memes are the ultimate source of information—particularly when they makes a biting point about something or some group that is not particularly favorably viewed. But it is well known that under the Roman Empire, Christianity did indeed adopt the pagan rituals of conquered peoples in an effort to help convert them. It worked pretty well as a strategy as it allowed the conquered peoples to continue a semblance of their observances as they remembered, and with time the population would be replaced with those who only knew the new traditions. This is not a secret. However, there are a few things wrong with the Ishtar meme that a simple Google search will turn up:

- Ishtar was the goddess of love and war and sex, as well as protection, fate, childbirth, marriage, and storms—there’s some fertility in there, but as with Aphrodite, there is also an element of power. Her cult practiced sacred prostitution, where women waited at a temple and had sex with a stranger in exchange for a divine blessing (and money to feed hungry children or pay a debt).

- Ishtar’s symbols were the the lion, the morning star, and eight or sixteen pointed stars—again, symbols of power.

- The word Easter does not appear to be derived from Ishtar, but from the German Eostre, the goddess of the dawn—a bringer of light. English and German are in the minority of languages that use a form of the word Easter to mark the holiday. Elsewhere, the observance is framed in Latin pascha, which in turn is derived from the Hebrew pesach, meaning of or associated with Passover. Ishtar and Easter appear to be homophones: they may be pronounced similarly, but have different meanings.

Our helpful meme places the egg in Ishtar’s domain, but Ishtar doesn’t seem to be connected to eggs in any explicit way. However, there are plenty of other older traditions that involve the egg as a symbol of rebirth and feature it prominently in creation mythologies:

- Ancient Egyptians believed in a primeval egg from which the sun god hatched. Alternatively, the sun was sometimes discussed as an egg itself, laid daily by the celestial goose, Seb, the god of the earth. The Phoenix is said to have emerged from this egg. The egg is also discussed in terms of a world egg, molded by Khnum from a lump of clay on his potter’s wheel (1).

- Hinduism makes a connection between the content of the egg and the structure of the universe: for example, the shell represents the heavens, the white the air, and the yolk the earth. The Chandogya Upanishads describes the act of creation in terms of the breaking of an egg:

The Sun is Brahma—this is the teaching. A further explanation thereof (is as follows). In the beginning this world was merely non-being. It was existent. It developed. It turned into an egg. It lay for the period of a year. It was split asunder. One of the two egg-shell parts became silver, one gold. That which was of silver is this earth. That which was of gold is the sky … Now what was born therefrom is yonder sun (1).

- In the Zoroastrian religion, the creation myth tells of an ongoing struggle between the principles of good and evil. During a lengthy truce of several thousand years, evil hurls himself into an abyss and good lays an egg, which represents the universe with the earth suspended from the vault of the sky at the midway point between where good and evil reside. Evil pierces the egg and returns to earth, and the two forces continue their battle (2).

- In Findland, Luonnotar, the Daughter of Nature floats on the waters of the sea, minding her own business when an eagle arrives, builds a nest on her knee, and lays several eggs. After a few days, the eggs begin to burn and Luonnotar jerks her knee away, causing the eggs to fall and break. The pieces form the world as we know it: the upper halves form the skies, the lower the earth, the yolks become the sun, and the whites become the moon (3).

- In China, there are several legends that hold a cosmic egg at their center, including the idea that the first being or certain people were born of eggs. For example, the Palangs trace their ancestry to a Naga princess who laid three eggs, and the Chin will not kill the king crow because it laid the original Chin egg from which they emerged (3).

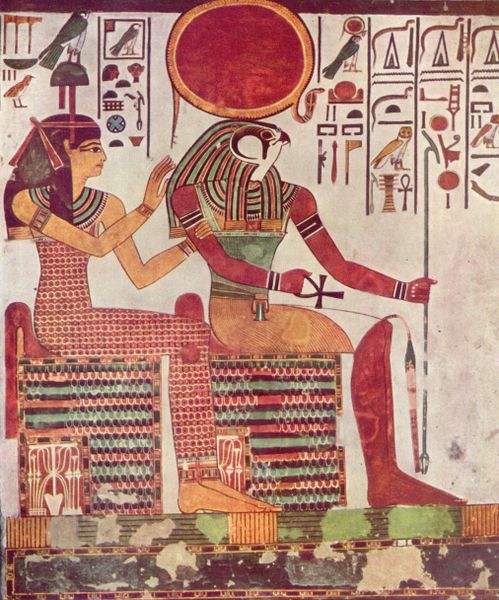

The Sun God, Ra with an egg-shaped disk over his head

These are some of the stories that build the foundation for the tradition of eggs at Easter. Contrary to the assertion of our meme, eggs and bunnies actually do have something to do with the idea of resurrection: in these early stories, the creator often emerged from the egg itself in some form:

The cosmic egg, according to the Vedic writings, has a spirit living within it which will be born, die, and be born yet again. Certain versions of the complicated Hindu mythology describe Prajapati as forming the egg and then appearing out of it himself. Brahma does likewise, and we find parallels in the ancient legends of Thoth and Ra. Egyptian pictures of Osiris, the resurrected corn god, show him returning to life once again rising up from the shell of a broken egg. The ancient legend of the Phoenix is similar. This beautiful mythical bird was said to live for hundreds of years. When its full span of life was completed it died in flames, rising again in a new form from the egg it had laid (4).

The Phoenix was adopted as a Christian symbol in the first century AD. It appears on funeral stones in early Christian art, churches, religious paintings, and stonework. The egg from which it rose has become our Easter egg. As with many symbols, the Easter egg has continued to shift. When the Lenten fast was adopted in the third and fourth centuries, observant Christians abstained from dairy products, including milk, cheese, butter, and eggs. In England, on the Saturday before Lent, it was common practice for children to go from door to door to beg for eggs—a last treat before the fast began.

Even the act of coloring eggs is tied to the idea of rebirth and resurrection. While egg decorating kits offer a vibrant means of decorating eggs today, the link between life and eggs was traditionally made by using a red coloring. Among Christians, red symbolizes the blood of Jesus. Among Macedonians, it has been a tradition to bring a red egg to Church and eat it when the priest proclaims “Christ is risen” at the Easter vigil and the Lenten fast is officially broken (5).

I love the Easter traditions at Church. The lighting of the Easter candle reminds me of my childhood Diwali celebrations and the lighting of Christmas lights as they all represent means of driving away darkness. Ishtar may well have some connection to the rites of Spring, and admittedly Easter itself is an observance of Spring, but in an age when so much wrong has been done in the name of religion, and religion is a focal point for criticism and debate, it’s worth remembering that the overlap of time and history has given us richer traditions than any of us can truly be aware of—and that memes shouldn’t be taken at face value.

Cited:

Newall, Venetia. (1967) “Easter Eggs,” The Journal of American Folklore Vol 80 (315): 3-32.

RE Hume, ed. (1931) The Thirteen Upanishads. London: 214-215

Notes: 1. Newall: 4 | 2. Hume: 214 | 3. Newall: 7 | 4. Newall: 14 | 5. Newall: 22

About the author: Krystal D’Costa is an anthropologist working in digital media in New York City. You can follow AiP on Facebook. Follow on Twitter @krystaldcosta.